Is it math built or is it discovered? Across the years the philosophy around mathematics can be divided in two big views in regards to how mathematical knowledge is constructed, formalism and platonism. If you believe that mathematics is discovered then you would be considered rather a platonist mathematician. On the contrary if you believe it is constructed then you are more a formalist. The goal of this article is to divulgate on this topic to non maths audience and hopefully at the end of it you can also take a position on it. Personally I tend to identify myself more with a platonist view but this is really personal, like cats or dogs.

One of the biggest logicians of all time, Kurt Gödel, who was a self-convinced platonist said:

[Platonism is] the view that mathematics describes a non-sensual reality, which exists independently both of the acts and [of] the dispositions of the human mind and is only perceived, and probably perceived very incompletely, by the human mind.

Gödel 1995, p. 323

Formalism on the other hand considers math just a game of symbols and manipulation from which we can infer new mathematical statements. In a mathematical theory we start with a set of axioms from which we start deriving results. For a formalist this game starts once we set the theory, that is the axioms are the rules of the game. Platonist on the other side believe axioms are obvious «truths» of our reality and try to discover other truths on top of that. For a formalist the term truth is a rather vague one and just refers to the things we discover in each theory. Platonists on the contrary believe mathematics is something that actually exist outside of our reasoning. Platonists discover what is already out there and formalists expand mathematical knowledge

Let’s get into some logic and proofs so you can get closer to the nature of mathematics.

Truth and provability

«Now it is raining»

Let’s consider this sentence which has nothing to do with maths, yet…

The sentence is easily provable or disprovable (unless you live in a cave). I can as I’m writing go outside and check… Well it is not raining then we have disproved and thus the sentence can be said to be false. But wait a minute, what if now you, the reader, don’t trust my assertion that this is false. Of course you can do the same I did. Go out and check for yourself. If you go out and find out it is raining then this sentence is true for you. The difference of course is the context and so it means truth is situation/context dependence this is key to understand what we consider truth in maths.

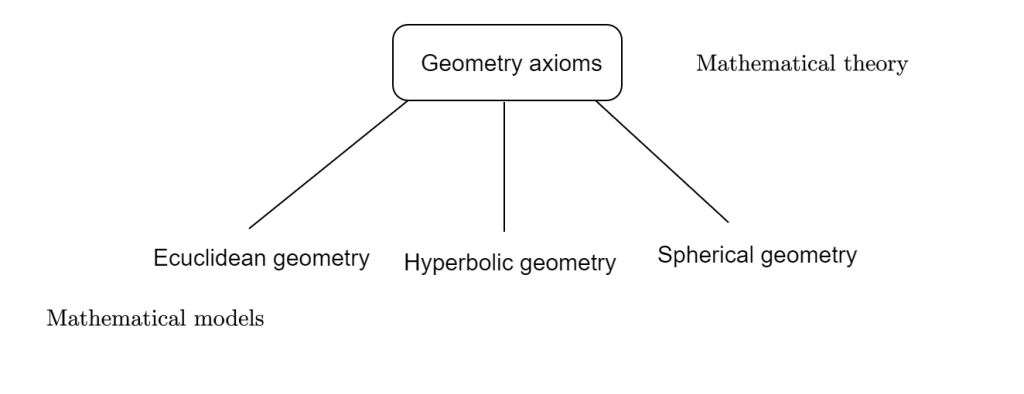

Moving now onto a more mathematical world. Let’s consider geometry: When geometry was axiomatized (Axiomatizing simply means giving basic truths) by Euclides a long time ago. There was one axiom that wasn’t included because it was thought to be not that obvious and so it was thought that probably was gonna be a consequence of the others. It was the parallel postulate which roughly says:

given a line L and point there exists just one line which does not intersect L

For many years mathematicians tried to prove this statement but all failed. At a certain point Gauss among other mathematicians showed there was an example of a geometry holding the 4 axioms but not holding the parallel postulate. That translates that this postulate is unprovable from the 4. It was the birth of the hyperbolic geometry.

In this model of geometry given a point and a line there’s always two lines which do not intersect the given line. What all this means is that as before with the sentence «Now it is raining» now the parallel postulate is model dependent. In Euclidean geometry (the typical one) we have to accept the parallel postulate as as axiom. A basic truth. On the contrary in hyperbolic geometry we take some other axioms apart from the basic four.

A mathematical theory is essentialy an amount of axioms and some kind of object where these object act. Then deriving from them we have mathematical models which are just instances of these theory. Which fulfill these axioms (and maybe more).

Basically we have seen that truth lives down in the models of a mathematical theory. And we consider a truth to be something provable, and the same with a falsehood and and a disproof.

Unprovable truths?

Warning! Things are about to get really confusing. Grab a tea or something relaxing and consider the following sentence:

«this sentence is false»

We are examining whether this sentence is true or false. If we consider it as false then by what it says means it is true. Similarly if it were true then its false. Then we find it is true and false at the same time in mathematics this would be called inconsistent as it doesnt obey the law of the excluded middle. That is the law that says, every sentence must be either true or false.

Making things weirder consider:

«this sentence is unprovable»

Let’s assume it is false then we have that the sentence is provable that means there is a proof for it meaning it is true. That is the sentence is true and the unprovable. Hold on, but have we just proved it ???

What happened here is the following, the word provable is in relation to some kind of axiom system unknown by just the sentence. We are observing and analyzing this sentence from outside this system in a meta-mathematical way. The way I see it is we proved its true from outside the mathematical theory this sentence is in (which we don’t know) but inside of this theory is unprovable.

This sentence is known as a Gödel sentence G. And Kürt Gödel used them in the proof of the biggest breakthroughs of logic in mathematics.

«Any consistent formal system F within which a certain amount of elementary arithmetic can be carried out is incomplete; i.e., there are statements of the language of F which can neither be proved nor disproved in F.«

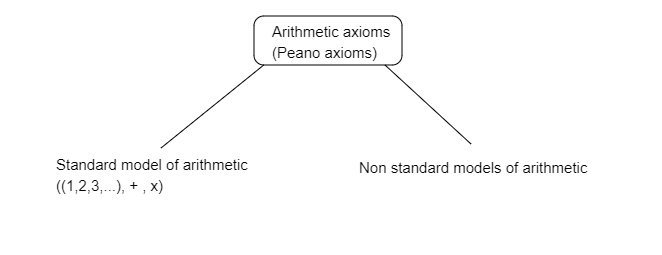

What the theorem tells us that any mathematical theory based on arithmetic is incomplete. Meaning there are certain statements about the natural numbers (1,2,3,…) which are not provable nor disprovable.

What Gödel did was he was able to construct a Gödel sentence which essentially said: «this arithmetic sentence is unprovable given the arithmetic axioms» which we have seen is true and thus unprovable.

I like to think about these result as a way of telling that we can giving some axioms to arithmetic we can just give as many proofs as a certain number but the number of sentences are actually infinite.

Also I like to think that what it has been traditionally said about natural numbers, they are the core behind arithmetic, were created by god and we, mortals, try to axiomatize them and derive all of its truths. Of course, do we really think we are that high to know all about them? I don’t think so. What we can is better axiomatize, find analogies, with other richer branches of mathematics to derive more and more results.

What Gödel did is basically construct a Gödel sentence G, inside the Standard model of arithmetic. As we have seen this sentence is true but unprovable within this model. Somewhat scary.